Open Close Principle is second principle from SOLID acronym.

Definition: Software entities (classes, modules, functions, etc.) should be open for extension, but closed for modification. That means if program needs to be changed it should be done without modification of existing code. When it is needed to change behavior of our program, it should be done with adding new classes and functionalities.

We can compare this principle to laptop. We have laptop with screen, keyboard and touchpanel, but we can easily extend our laptop by adding mouse or external keyboard or even extra screen without modification construction of our laptop.

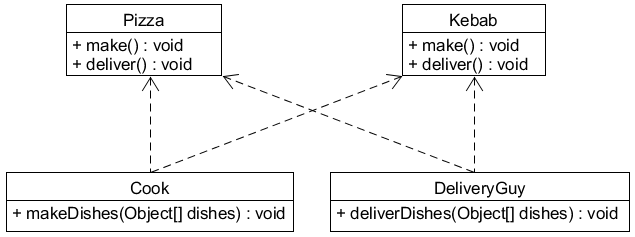

Let’s see this principle in action. Below is simple application not compliant with Open Close Principle. First we have two classes, Pizza and Kebab, which have two public methods.

public class Pizza {

public void make() {

System.out.println("Make pizza.");

}

public void deliver() {

System.out.println("Deliver pizza.");

}

}

public class Kebab {

public void make() {

System.out.println("Make kebab.");

}

public void deliver() {

System.out.println("Deliver kebab.");

}

}

These classes are used by Cook class and DeliveryGuy class.

public class Cook {

public void makeDishes(Object[] dishes) {

for(Object dish : dishes) {

if(dish instanceof Pizza) {

((Pizza) dish).make();

} else if(dish instanceof Kebab) {

((Kebab) dish).make();

}

}

}

}

public class DeliveryGuy {

public void deliverDishes(Object[] dishes) {

for(Object dish : dishes) {

if(dish instanceof Pizza) {

((Pizza) dish).deliver();

} else if(dish instanceof Kebab) {

((Kebab) dish).deliver();

}

}

}

}

Let’s also take a look on UML diagram to see what is going on here.

Let’s run this app.

public static void main(String[] args) {

Cook cook = new Cook();

DeliveryGuy deliveryGuy = new DeliveryGuy();

Object[] dishes = new Object[] {new Pizza(), new Kebab()};

cook.makeDishes(dishes);

deliveryGuy.deliverDishes(dishes);

}

After running app we can see that all dishes are made and delivered.

Make pizza.

Make kebab.

Deliver pizza.

Deliver kebab.

Process finished with exit code 0

Now let’s see what happens when we need to add some changes to this program. For example let’s assume that our client wants us to add a Hamburger class to our app. No problem, let’s do that. First we need to write this new class.

public class Hamburger {

public void make() {

System.out.println("Make hamburger.");

}

public void deliver() {

System.out.println("Deliver hamburger.");

}

}

Great, then we need to update our existing classes.

public class Cook {

public void makeDishes(Object[] dishes) {

for(Object dish : dishes) {

if(dish instanceof Pizza) {

((Pizza) dish).make();

} else if(dish instanceof Kebab) {

((Kebab) dish).make();

} else if(dish instanceof Hamburger) {

((Hamburger) dish).make();

}

}

}

}

We also need to update our main program.

public static void main(String[] args) {

Cook cook = new Cook();

DeliveryGuy deliveryGuy = new DeliveryGuy();

Object[] dishes = new Object[] {new Pizza(), new Kebab(), new Hamburger()};

cook.makeDishes(dishes);

deliveryGuy.deliverDishes(dishes);

}

After finishing updating our code, we can run the program.

Make pizza.

Make kebab.

Make hamburger.

Deliver pizza.

Deliver kebab.

Process finished with exit code 0

Oh dear, something went wrong. Our Cook made all dishes along with our new hamburger but our DeliveryGuy has not delivered ordered hamburger. Of course, now we see what the problem is, we forgot to modify our DeliveryGuy class. This is why applications which are not written according to Open Close Principle are so vulnerable to mistakes. If we need to add some new functionalities, we need to update a lot of existing code.

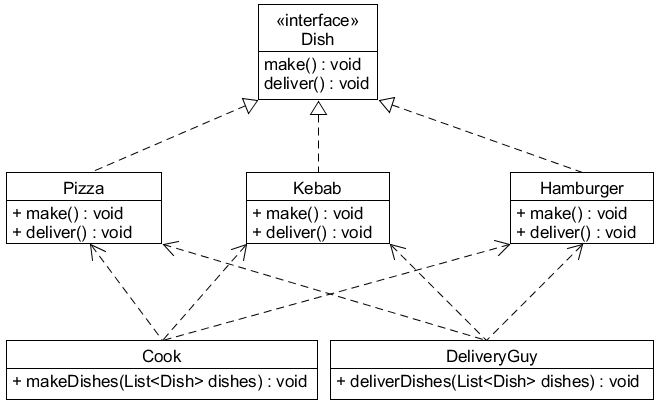

Let’s change our program to be compliant with OCP. First let’s add an interface so we will be sure that all methods will be implemented in each new dish.

public interface Dish {

void make();

void deliver();

}

Voilà. Now we need to add to our classes implementation of this interface.

public class Pizza implements Dish {

public void make() {

System.out.println("Make pizza.");

}

public void deliver() {

System.out.println("Deliver pizza.");

}

}

public class Kebab implements Dish {

public void make() {

System.out.println("Make kebab.");

}

public void deliver() {

System.out.println("Deliver kebab.");

}

}

public class Hamburger implements Dish {

public void make() {

System.out.println("Make hamburger.");

}

public void deliver() {

System.out.println("Deliver hamburger.");

}

}

Looks good. Now we need to change our Cook class and DeliveryGuy class to use List of Dishes instead of array of objects.

import java.util.List;

public class Cook {

public void makeDishes(List<Dish> dishes) {

for(Dish dish : dishes) {

dish.make();

}

}

}

import java.util.List;

public class DeliveryGuy {

public void deliverDishes(List<Dish> dishes) {

for(Dish dish : dishes) {

dish.deliver();

}

}

}

Good, now if we need to add new dish we will not change code for Cook class and DeliveryGuy class. Finally, let’s not forget about changing our main program.

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.Arrays;

import java.util.List;

public class MyFabulousRestaurant {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Cook cook = new Cook();

DeliveryGuy deliveryGuy = new DeliveryGuy();

List<Dish> dishes = new ArrayList<>(Arrays.asList(new Pizza(), new Kebab(), new Hamburger()));

cook.makeDishes(dishes);

deliveryGuy.deliverDishes(dishes);

}

}

And what happens when we run our app?

Make pizza.

Make kebab.

Make hamburger.

Deliver pizza.

Deliver kebab.

Deliver hamburger.

Process finished with exit code 0

Just as we expected all dishes were made and delivered. Let’s see how our app looks like in UML diagram.

To sum up, when we are gathering requirements from our customer we always need to think if our program would be extended in the future and we should use polymorphism instead of if…else ladder.