Liskov Substitution Principle is third principle from SOLID acronym. It is named after Barbara Liskov, another name of this principle is Behavioral Subtyping and the definition is: The principle that subclasses should satisfy the expectations of clients accessing subclass objects through references of superclass type, not just as regards syntactic safety (such as absence of „method-not-found” errors) but also as regards behavioral correctness.

Another words the principle says that if class S, subtype, is a child class of D type then objects of type D might be replaced with objects of type S without breaking the program. That means if there is any subtyping relation, like inheritance, we should be able to use child classes in place of parent class interchangeably and it should not break the program in any way. By breaking the program we understand that it will not throw any exception and when we are making the replacement our program will behave properly.

In real-life this principle can be compared to cars. Car is our parent class, we know how a car should behave and how it works. Each car model is our subtype, child class, so it behaves like a car. This means that if we know how to drive a car, we should be able to drive any car model without any major surprises.

Let’s take a look on our code from Open Close Principle. This code is not consistent with Liskov Substitution Principle. We will change that. First our interface Dish, which has two methods, make and deliver.

public interface Dish {

void make();

void deliver();

}

And we have three dishes, Pizza, Kebab and Hamburger, which implement interface Dish.

public class Pizza implements Dish {

public void make() {

System.out.println("Make pizza.");

}

public void deliver() {

System.out.println("Deliver pizza.");

}

}

public class Kebab implements Dish {

public void make() {

System.out.println("Make kebab.");

}

public void deliver() {

System.out.println("Deliver kebab.");

}

}

public class Hamburger implements Dish {

public void make() {

System.out.println("Make hamburger.");

}

public void deliver() {

System.out.println("Deliver hamburger.");

}

}

Then we have two classes, Cook and DeliveryGuy. Cook makes dishes and DeliveryGuy delivers dishes.

import java.util.List;

public class Cook {

public void makeDishes(List<Dish> dishes) {

for(Dish dish : dishes) {

dish.make();

}

}

}

import java.util.List;

public class DeliveryGuy {

public void deliverDishes(List<Dish> dishes) {

for(Dish dish : dishes) {

dish.deliver();

}

}

}

And our program. We have cook which is object of Cook, deliveryGuy which is object of DeliveryGuy, dishes which are List of Dishes. Then cook makes dishes and deliveryGuy delivers dishes.

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.Arrays;

import java.util.List;

public class MyFabulousRestaurant {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Cook cook = new Cook();

DeliveryGuy deliveryGuy = new DeliveryGuy();

List<Dish> dishes = new ArrayList<>(Arrays.asList(new Pizza(), new Kebab(), new Hamburger()));

cook.makeDishes(dishes);

deliveryGuy.deliverDishes(dishes);

}

}

Let’s run our program.

Make pizza.

Make kebab.

Make hamburger.

Deliver pizza.

Deliver kebab.

Deliver hamburger.

Process finished with exit code 0

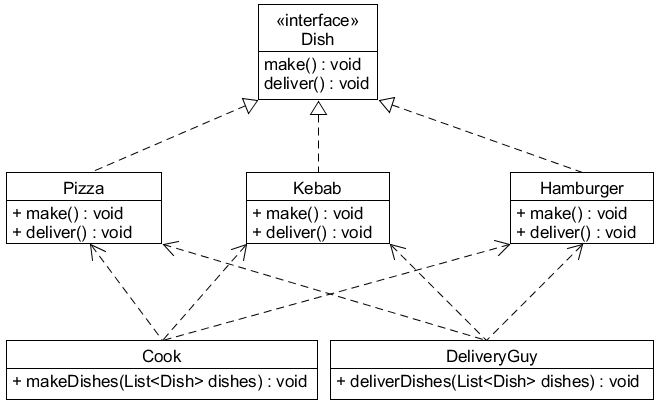

Good, all dishes are made and delivered. Let’s take a look at UML diagram.

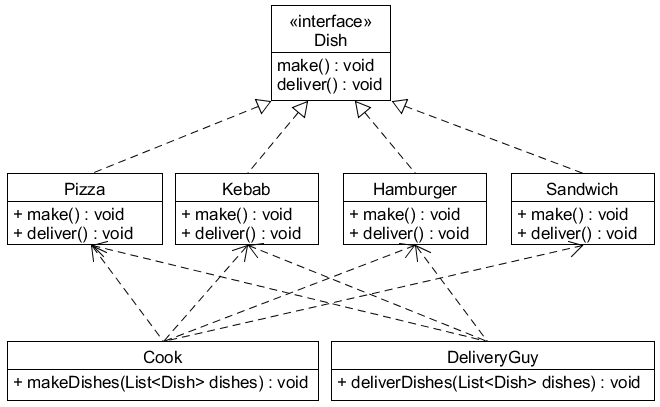

There is nothing disturbing here but in our restaurant our cook and deliveryGuy need to eat something during they work hours. So let’s add new dish, for example Sandwich. Sandwich will implement interface Dish so it will have two methods, make and deliver. Cook needs to make Sandwich but deliveryGuy cannot deliver it because Sandwich is not in menu so customers cannot order it. Let’s see this on UML diagram.

Now we have a problem with deliver method in Sandwich class and we have three options, all of them are bad. First option, we can just leave this method empty.

public class Sandwich implements Dish {

public void make() {

System.out.println("Make sandwich.");

}

public void deliver() {

}

}

Second option, we can add some message in console.

public class Sandwich implements Dish {

public void make() {

System.out.println("Make sandwich.");

}

public void deliver() {

System.out.println("Method should not be used.");

}

}

Third option, we can throw an exception.

public class Sandwich implements Dish {

public void make() {

System.out.println("Make sandwich.");

}

public void deliver() {

try {

throw new Exception();

} catch (Exception e) {

throw new RuntimeException(e);

}

}

}

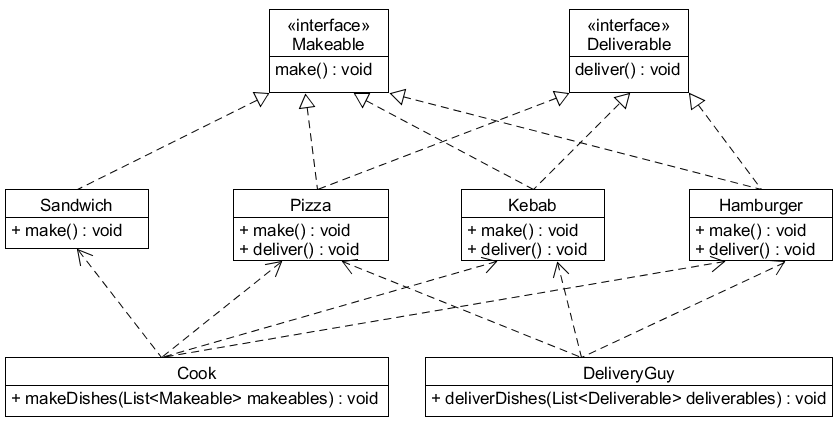

As we could see, class Sandwich does not need to implement deliver method so we should change our code to be consistent with Liskov Substitution Principle. First we separate interface Dish into two new interfaces, Makeable and Deliverable.

public interface Makeable {

void make();

}

public interface Deliverable {

void deliver();

}

Then we implements these two interfaces in our old dishes.

public class Pizza implements Makeable, Deliverable {

public void make() {

System.out.println("Make pizza.");

}

public void deliver() {

System.out.println("Deliver pizza.");

}

}

public class Kebab implements Makeable, Deliverable {

public void make() {

System.out.println("Make kebab.");

}

public void deliver() {

System.out.println("Deliver kebab.");

}

}

public class Hamburger implements Makeable, Deliverable {

public void make() {

System.out.println("Make hamburger.");

}

public void deliver() {

System.out.println("Deliver hamburger.");

}

}

And our new dish Sandwich will implement only Makeable interface.

public class Sandwich implements Makeable {

public void make() {

System.out.println("Make sandwich.");

}

}

Let’s not forget to change our Cook class, DeliverGuy class and our main program.

import java.util.List;

public class Cook {

public void makeDishes(List<Makeable> makeables) {

for(Makeable makeable : makeables) {

makeable.make();

}

}

}

import java.util.List;

public class DeliveryGuy {

public void deliverDishes(List<Deliverable> deliverables) {

for(Deliverable deliverable : deliverables) {

deliverable.deliver();

}

}

}

import java.util.ArrayList;

import java.util.Arrays;

import java.util.List;

public class MyFabulousRestaurant {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Cook cook = new Cook();

DeliveryGuy deliveryGuy = new DeliveryGuy();

List<Makeable> makeables = new ArrayList<>(Arrays.asList(new Pizza(), new Kebab(), new Hamburger(), new Sandwich()));

List<Deliverable> deliverables = new ArrayList<>(Arrays.asList(new Pizza(), new Kebab(), new Hamburger()));

cook.makeDishes(makeables);

deliveryGuy.deliverDishes(deliverables);

}

}

And after running the program everything works like it should.

Make pizza.

Make kebab.

Make hamburger.

Make sandwich.

Deliver pizza.

Deliver kebab.

Deliver hamburger.

Process finished with exit code 0

In the end, let’s see UML diagram.

Preconditions

There are also two other versions of LSP. First one is about preconditions. Let’s take our Hamburger class, it will be our parent class which looks like below. It has one public method that calculates total price according to price and discount. It also has a precondition, we do not want to sell hamburgers that are cheeper than 2.50. If price is less or equal to 2.5 our program throws an exception.

public class Hamburger {

public float calculateTotalPrice(float price, float discount) throws Exception {

if(price <= 2.5) throw new Exception();

return price * (100 - discount) / 100;

}

}

In our Fabulous Restaurant we sell couple types of hamburgers, one of them is Doubleburger. Let’s see this class. It is a child class of Hamburger class and it has also one public method that is overriden. We do not want to sell doubleburgers with discount that is larger or equal to 20%. So we strengthen the precondition.

public class Doubleburger extends Hamburger {

public float calculateTotalPrice(float price, float discount) throws Exception {

if(price <= 2.5 || discount >= 20) throw new Exception();

return price * (100 - discount) / 100;

}

}

Above example breaks LSP because we cannot replace parent class (Hamburger) with child class (Doubleburger). This became a rule which tells that preconditions cannot be strengthened in subtypes. We can weaken preconditions in subtypes.

Postconditions

Second rule is about postconditions. Let’s add to our Hamburger class a postcondition which checks if totalPrice is less or equal to 0, if it is, it throws an exception.

public class Hamburger {

public float calculateTotalPrice(float price, float discount) throws Exception {

if(price <= 2.5) throw new Exception();

float totalPrice = price * (100 - discount) / 100;

if(totalPrice <= 0) throw new Exception();

return totalPrice;

}

}

In our Doubleburger class let’s delete precondition without adding any postcondition.

public class Doubleburger extends Hamburger {

public float calculateTotalPrice(float price, float discount) throws Exception {

float totalPrice = price * (100 - discount) / 100;

return totalPrice;

}

}

This is not acceptable because if we use child class in place of parent class when total price is less or equal 0 it will not throw any exception and that is not what we want. This rule tells that postconditions cannot be weakened in subtypes.

In summary we should always think about polymorphic replacement of the base class when we inherit it. When we design our system we should think if we can be able to use base and child classes interchangeably.